Blog: Articles on Psychological Wellbeing, Relationships, Brain Health, Counselling and Neurofeedback

Welcome to the blog of Sojourn Counselling and Neurofeedback. Articles posted here are written by our clinical staff and relate to services we offer or conditions we address. We hope they will be helpful to you in some way, whether you're considering counselling for yourself or someone else, gathering information on a mental health related issue, or just want to find out more about who we are and what we do.

Do you ever find yourself in a situation when your mind goes blank? Maybe you experience your mind suddenly racing and you can’t decide amoung the myriad of thoughts blasting your consciousness which to focus on. I would venture to say that this happens to most people to some degree, but perhaps it seems to be happening more frequently or intensely for you recently.

Trauma Primes the Nervous System

The nervous system is sensitively tuned to detect threat and recruit biological systems toward self preservation. You may have observed an animal that suddenly becomes very still and appears almost lifeless for a seemingly impossible duration when it detects a sound or sudden movement in its environment. Its nervous system has prepared it to elude detection or suddenly flee the scene in the presence of a predator. You may even recall a time when you’ve felt threatened in some way and all your senses become highly tuned to detect sound or movement in your environment.

This is evidence that the sympathetic branch of your nervous system has activated. It responds instinctively to direct internal resources to those systems necessary for survival. In this way heart rate increases, sweat glands activate, muscles tense, digestion slows, pupils dilate, etc. The body is gearing up for action - either to attack or get out of harm’s way as fast as possible. This “fight or flight response” activates without conscious intervention.

In special circumstances, the nervous system determines that doing anything at all will increase the risk of harm and shuts all systems down. You may notice this when an animal appears dead in the face of a lethal predator. Perhaps you recall an incident when you seemed frozen, unable to speak, move, or even think. This was an unconscious decision your biological systems made for you because to deliberate may have meant destruction.

Amazingly, after a traumatic event, the nervous system tunes itself to even more efficient responding in preparation for some similar threat. It’s as if the systems’ leader says to the components, “Whatever we did to survive worked, but we may not be so lucky next time” and the neural networks involved in detection and response are reorganized for the “next time.”

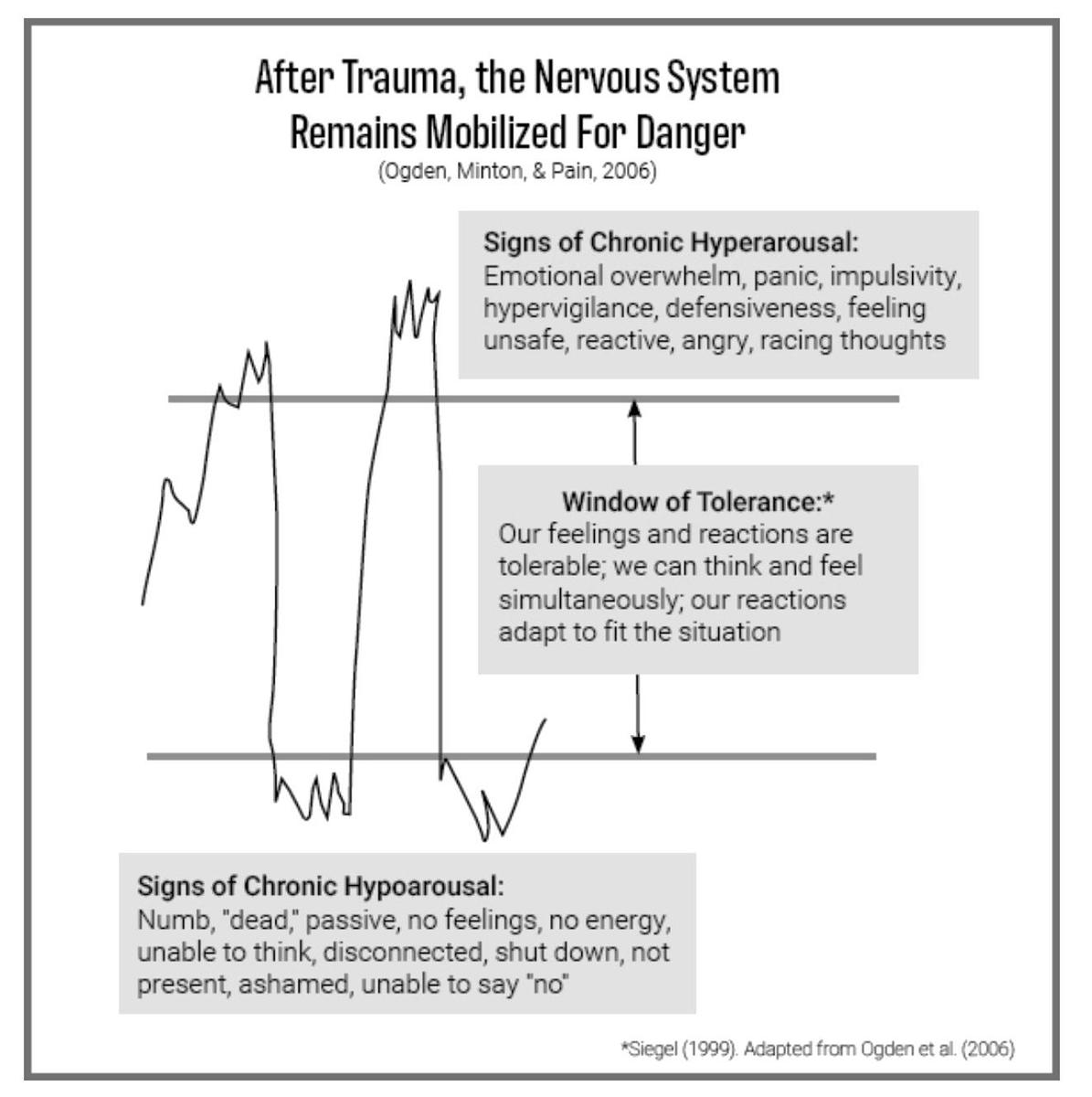

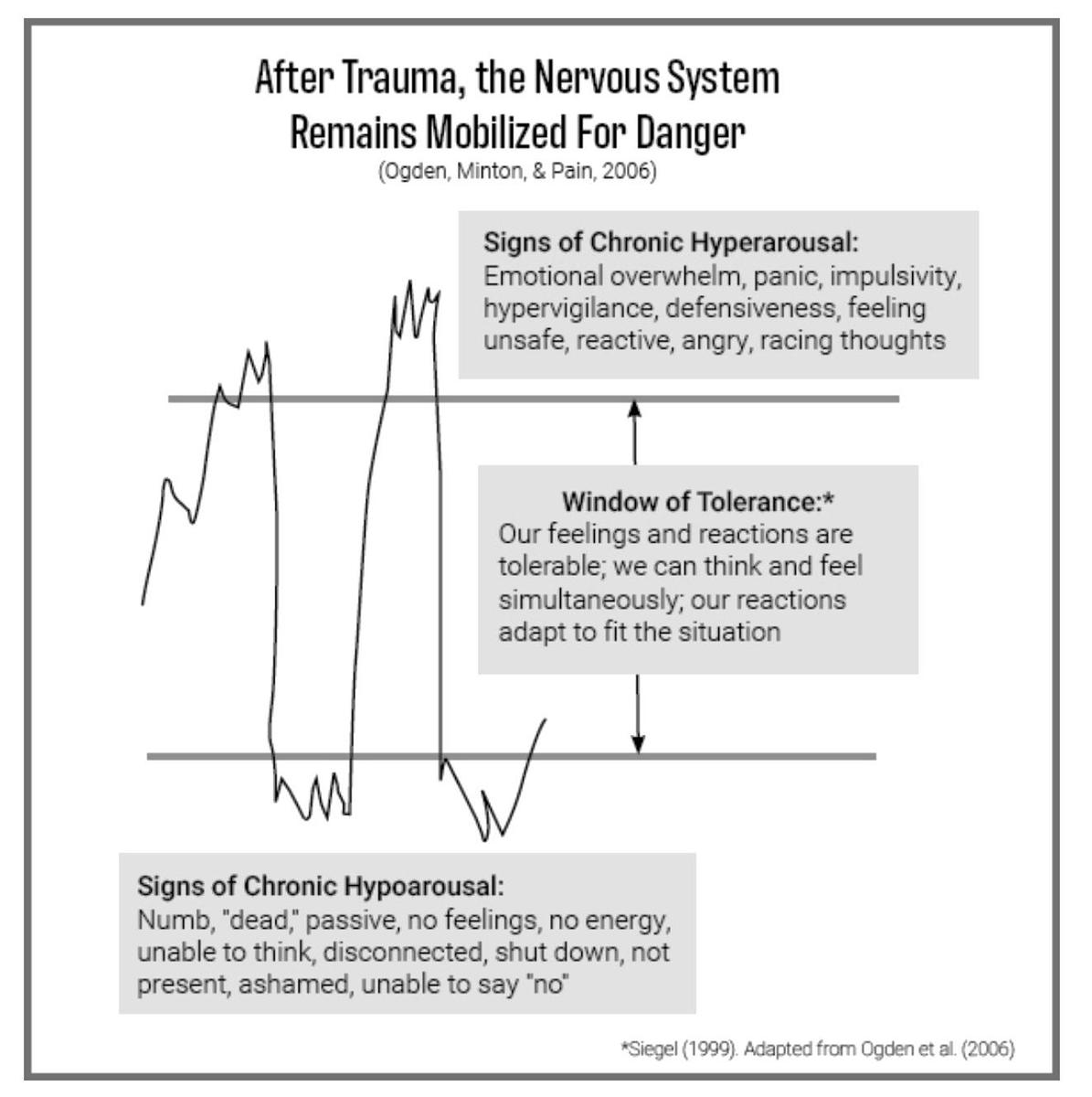

The problem is that the nervous system is now so primed for a response to threat, it activates at the slightest perception of danger. The consequence to this hypervigilance is exhaustion and fatigue because the fight, flight or freeze response is very energy-demanding. Another consequence is self-blame and regret as these reactions, though appropriate if the threat were real, can have us react in ways that are embarrassing or disruptive to relationships. This illustration taken from Janina Fisher’s book, Transforming the Living Legacy of Trauma (2021) and adapted from Dan Siegel’s concept of the river of integration shows how the nervous system adapts itself to the stress response.

The Chronically Stressed Nervous System

For much of the time, our autonomic nervous systems remain within the window of tolerance. We may experience increased activation when excited and decreased activation when relaxed. These states fluctuate fluidly relative to the situations we face throughout the day. Situations and emotions experienced while within the window are manageable, meaning we can continue to think and make decisions when under stress. Under extreme situations, the nervous system jumps into a state of overwhelm or shut down and we get stuck there for a while. When we experience a very extreme stressor like a near-death situation, this window narrows and we may find ourselves in states of hyper- or hypoarousal more frequently. The window of tolerance also narrows in those of us who are regularly exposed to stress, such as growing up in a volatile home. As the window narrows, the nervous system reacts to events that have a low probability of danger.

Fisher says that because the brain responds to threat before we are aware of it, it is near impossible to choose how to respond. Trauma survivors can find themselves acting impulsively and often feel ashamed for it. Turning to substances is common for those who find their nervous systems chronically either hyper- or hypoaroused. While these can help the brain return to the window of tolerance, this relief is temporary and dependence on these substances/behaviours to feel normal develops. When triggered, a traumatized individual may use perfectionism, workaholism, food, self-harm, suicidal behaviour, alcohol and other substances to get themselves back into the window of tolerance.

Fisher says that because the brain responds to threat before we are aware of it, it is near impossible to choose how to respond. Trauma survivors can find themselves acting impulsively and often feel ashamed for it. Turning to substances is common for those who find their nervous systems chronically either hyper- or hypoaroused. While these can help the brain return to the window of tolerance, this relief is temporary and dependence on these substances/behaviours to feel normal develops. When triggered, a traumatized individual may use perfectionism, workaholism, food, self-harm, suicidal behaviour, alcohol and other substances to get themselves back into the window of tolerance.

The space or window between hyperarousal and hypoarousal is not the same for everyone. Those who have experienced a life-threatening accident, illness, natural disaster, or crime may have a narrowed window. Additionally, those who have experienced chronic abuse may have a highly sensitive nervous system and narrow window of tolerance. We often see this in individuals with complex post-traumatic stress disorder (c-PTSD). In such cases, it doesn’t take much for the nervous system to become either highly activated or shut down. This is one of the pitfalls of neuroplasticity.

Good News: The Brain can Change

Neuroplasticity is the term for the brain’s capacity to change over time and is a biological mechanism of learning. Experience elicits structural (growth of new nerve cells) and functional (more efficient connections between cells) changes in the brain, which are accelerated under extreme stress. This is an adaptation to be better poised to escape destruction “next time.” As a result however, the brain activates at the slightest hint of danger, the far majority of which are false alarms. Chronic stress results in the narrowing of the window of tolerance, the experience of which is frequent hyperaroused or hypoaroused states. When hyperaroused, a person feels on edge, reactive, overwhelmed and acts impulsively. When hypoaroused we feel numb, emotionless, distant from ourselves and others, compliant, and shut down. In PTSD survivors and those who have experienced chronic stress, the mechanisms of neuroplasticity have tuned the brain to more easily enter these states.

The good news of neuro-plasticity is that the brain can also change to widen the window of tolerance. Neurofeedback is a tool we use at Sojourn to encourage the brain to change in this way.

Neurofeedback Therapy Improves Emotional Resilience

One of the neurotherapy tools we use is called NeurOptimal. This technology uses the electroencephalogram (EEG) to monitor the brain’s activity and feed back information about when and how this activity is changing.

A healthy brain is always changing flexibly to environmental stimuli, becoming more active or less active as necessary to remain within the window of tolerance. This helps us orient to events in the vicinity that require attention. Using focus as an example, we are frequently shifting from a narrow focus like that necessary when reading something, to an open focus to take in more of our surroundings and locate the source when we hear someone speak to us.

We need increased activation/arousal when having to perform at some physical or mental task and decreased arousal when relaxing or going to sleep. The NeurOptimal system detects when the brain is about to shift states, in the direction of either side of the window of tolerance for example, and gives the brain feedback in these moments. This kind of feedback, when delivered repetitively, trains a kind of self-awareness. The NeurOptimal system lets the brain know when it is about to change trajectory, toward increased arousal or decreased arousal. When this feedback is delivered repeatedly, the brain becomes increasingly aware of those moments when it is shifting state. This is important because these state shifts can become reactionary, particularly for the brain that is often stressed. With this kind of neurofeedback therapy and the resultant increased self-awareness, the brain is better able to determine whether a shift is truly necessary and course-correct when appropriate. In this way the brain is better able to adapt to changes in the environment.

NeurOptimal training helps the brain become more flexible, but it also encourages increased resilience. While the brain needs to change to an ever-changing environment, too much change too quickly can result in movement outside the window of tolerance. For those of us who have experienced emotional overwhelm or numbing, we know that it is near impossible to perform optimally when in these states. It is difficult to decide which thoughts to communicate when the mind is racing. Conversely, when there are no thoughts apparent and the mind is shut down, it is extremely difficult to say or do anything. When the brain learns to recognize when it is shifting trajectory, it becomes more resilient to slipping all the way into these extreme states.

Some have likened NeurOptimal’s feedback to rumble strips on the highway. These give drivers vibration feedback that the car is moving out of the lane, either towards the shoulder or into oncoming traffic. This feedback occurs regardless of whether drivers are asleep at the wheel or intending to cross the line and pull over or pass a slower moving vehicle. This feedback is invaluable to maintaining a safe course when distracted or falling asleep.

Similarly, there are moments when it is necessary and appropriate for the brain to become more or less aroused. But the traumatized brain detects danger where there is none and too quickly shifts towards extreme responses. Similar to the vibration feedback of the rumble strips on the road, NeurOptimal gives the brain feedback when it is changing trajectory giving it the opportunity to course-correct if necessary. Over time, the brain becomes better able to determine its trajectory and adjust itself accordingly. Gradually as one continues to train the brain, a person’s window of tolerance widens, becoming more resilient to subtle stressors and more flexible to shift states as required.

Our clients undergoing neurofeedback therapy tell us that they find themselves becoming overwhelmed and shut down less often and that they are better able to return to a restful baseline after stressful events. They tell us that they become more aware of their nervous systems’ responses to stress and can therefore make better choices to limit exposure to stressors. They are more responsive to their circumstances and find themselves reacting less. This means that there is less relational “clean up” to do. Over time, the window of tolerance widens and life and relationships become more manageable.

If you would like to experience the impact NeurOptimal neurofeedback can have on your window of tolerance, set up an appointment with one of our trainers today.

We also have systems you can rent and do neurofeedback at home. Email us if you prefer to rent a neurofeedback system.

Sojourn Counselling and Neurofeedback serves the Greater Vancouver and the Fraser Valley regions from our office in Cloverdale, Surrey, BC.

Do you ever find yourself in a situation when your mind goes blank? Maybe you experience your mind suddenly racing and you can’t decide amoung the myriad of thoughts blasting your consciousness which to focus on. I would venture to say that this happens to most people to some degree, but perhaps it seems to be happening more frequently or intensely for you recently.

Trauma Primes the Nervous System

The nervous system is sensitively tuned to detect threat and recruit biological systems toward self preservation. You may have observed an animal that suddenly becomes very still and appears almost lifeless for a seemingly impossible duration when it detects a sound or sudden movement in its environment. Its nervous system has prepared it to elude detection or suddenly flee the scene in the presence of a predator. You may even recall a time when you’ve felt threatened in some way and all your senses become highly tuned to detect sound or movement in your environment.

This is evidence that the sympathetic branch of your nervous system has activated. It responds instinctively to direct internal resources to those systems necessary for survival. In this way heart rate increases, sweat glands activate, muscles tense, digestion slows, pupils dilate, etc. The body is gearing up for action - either to attack or get out of harm’s way as fast as possible. This “fight or flight response” activates without conscious intervention.

In special circumstances, the nervous system determines that doing anything at all will increase the risk of harm and shuts all systems down. You may notice this when an animal appears dead in the face of a lethal predator. Perhaps you recall an incident when you seemed frozen, unable to speak, move, or even think. This was an unconscious decision your biological systems made for you because to deliberate may have meant destruction.

Amazingly, after a traumatic event, the nervous system tunes itself to even more efficient responding in preparation for some similar threat. It’s as if the systems’ leader says to the components, “Whatever we did to survive worked, but we may not be so lucky next time” and the neural networks involved in detection and response are reorganized for the “next time.”

The problem is that the nervous system is now so primed for a response to threat, it activates at the slightest perception of danger. The consequence to this hypervigilance is exhaustion and fatigue because the fight, flight or freeze response is very energy-demanding. Another consequence is self-blame and regret as these reactions, though appropriate if the threat were real, can have us react in ways that are embarrassing or disruptive to relationships. This illustration taken from Janina Fisher’s book, Transforming the Living Legacy of Trauma (2021) and adapted from Dan Siegel’s concept of the river of integration shows how the nervous system adapts itself to the stress response.

The Chronically Stressed Nervous System

For much of the time, our autonomic nervous systems remain within the window of tolerance. We may experience increased activation when excited and decreased activation when relaxed. These states fluctuate fluidly relative to the situations we face throughout the day. Situations and emotions experienced while within the window are manageable, meaning we can continue to think and make decisions when under stress. Under extreme situations, the nervous system jumps into a state of overwhelm or shut down and we get stuck there for a while. When we experience a very extreme stressor like a near-death situation, this window narrows and we may find ourselves in states of hyper- or hypoarousal more frequently. The window of tolerance also narrows in those of us who are regularly exposed to stress, such as growing up in a volatile home. As the window narrows, the nervous system reacts to events that have a low probability of danger.

Fisher says that because the brain responds to threat before we are aware of it, it is near impossible to choose how to respond. Trauma survivors can find themselves acting impulsively and often feel ashamed for it. Turning to substances is common for those who find their nervous systems chronically either hyper- or hypoaroused. While these can help the brain return to the window of tolerance, this relief is temporary and dependence on these substances/behaviours to feel normal develops. When triggered, a traumatized individual may use perfectionism, workaholism, food, self-harm, suicidal behaviour, alcohol and other substances to get themselves back into the window of tolerance.

Fisher says that because the brain responds to threat before we are aware of it, it is near impossible to choose how to respond. Trauma survivors can find themselves acting impulsively and often feel ashamed for it. Turning to substances is common for those who find their nervous systems chronically either hyper- or hypoaroused. While these can help the brain return to the window of tolerance, this relief is temporary and dependence on these substances/behaviours to feel normal develops. When triggered, a traumatized individual may use perfectionism, workaholism, food, self-harm, suicidal behaviour, alcohol and other substances to get themselves back into the window of tolerance.

The space or window between hyperarousal and hypoarousal is not the same for everyone. Those who have experienced a life-threatening accident, illness, natural disaster, or crime may have a narrowed window. Additionally, those who have experienced chronic abuse may have a highly sensitive nervous system and narrow window of tolerance. We often see this in individuals with complex post-traumatic stress disorder (c-PTSD). In such cases, it doesn’t take much for the nervous system to become either highly activated or shut down. This is one of the pitfalls of neuroplasticity.

Good News: The Brain can Change

Neuroplasticity is the term for the brain’s capacity to change over time and is a biological mechanism of learning. Experience elicits structural (growth of new nerve cells) and functional (more efficient connections between cells) changes in the brain, which are accelerated under extreme stress. This is an adaptation to be better poised to escape destruction “next time.” As a result however, the brain activates at the slightest hint of danger, the far majority of which are false alarms. Chronic stress results in the narrowing of the window of tolerance, the experience of which is frequent hyperaroused or hypoaroused states. When hyperaroused, a person feels on edge, reactive, overwhelmed and acts impulsively. When hypoaroused we feel numb, emotionless, distant from ourselves and others, compliant, and shut down. In PTSD survivors and those who have experienced chronic stress, the mechanisms of neuroplasticity have tuned the brain to more easily enter these states.

The good news of neuro-plasticity is that the brain can also change to widen the window of tolerance. Neurofeedback is a tool we use at Sojourn to encourage the brain to change in this way.

Neurofeedback Therapy Improves Emotional Resilience

One of the neurotherapy tools we use is called NeurOptimal. This technology uses the electroencephalogram (EEG) to monitor the brain’s activity and feed back information about when and how this activity is changing.

A healthy brain is always changing flexibly to environmental stimuli, becoming more active or less active as necessary to remain within the window of tolerance. This helps us orient to events in the vicinity that require attention. Using focus as an example, we are frequently shifting from a narrow focus like that necessary when reading something, to an open focus to take in more of our surroundings and locate the source when we hear someone speak to us.

We need increased activation/arousal when having to perform at some physical or mental task and decreased arousal when relaxing or going to sleep. The NeurOptimal system detects when the brain is about to shift states, in the direction of either side of the window of tolerance for example, and gives the brain feedback in these moments. This kind of feedback, when delivered repetitively, trains a kind of self-awareness. The NeurOptimal system lets the brain know when it is about to change trajectory, toward increased arousal or decreased arousal. When this feedback is delivered repeatedly, the brain becomes increasingly aware of those moments when it is shifting state. This is important because these state shifts can become reactionary, particularly for the brain that is often stressed. With this kind of neurofeedback therapy and the resultant increased self-awareness, the brain is better able to determine whether a shift is truly necessary and course-correct when appropriate. In this way the brain is better able to adapt to changes in the environment.

NeurOptimal training helps the brain become more flexible, but it also encourages increased resilience. While the brain needs to change to an ever-changing environment, too much change too quickly can result in movement outside the window of tolerance. For those of us who have experienced emotional overwhelm or numbing, we know that it is near impossible to perform optimally when in these states. It is difficult to decide which thoughts to communicate when the mind is racing. Conversely, when there are no thoughts apparent and the mind is shut down, it is extremely difficult to say or do anything. When the brain learns to recognize when it is shifting trajectory, it becomes more resilient to slipping all the way into these extreme states.

Some have likened NeurOptimal’s feedback to rumble strips on the highway. These give drivers vibration feedback that the car is moving out of the lane, either towards the shoulder or into oncoming traffic. This feedback occurs regardless of whether drivers are asleep at the wheel or intending to cross the line and pull over or pass a slower moving vehicle. This feedback is invaluable to maintaining a safe course when distracted or falling asleep.

Similarly, there are moments when it is necessary and appropriate for the brain to become more or less aroused. But the traumatized brain detects danger where there is none and too quickly shifts towards extreme responses. Similar to the vibration feedback of the rumble strips on the road, NeurOptimal gives the brain feedback when it is changing trajectory giving it the opportunity to course-correct if necessary. Over time, the brain becomes better able to determine its trajectory and adjust itself accordingly. Gradually as one continues to train the brain, a person’s window of tolerance widens, becoming more resilient to subtle stressors and more flexible to shift states as required.

Our clients undergoing neurofeedback therapy tell us that they find themselves becoming overwhelmed and shut down less often and that they are better able to return to a restful baseline after stressful events. They tell us that they become more aware of their nervous systems’ responses to stress and can therefore make better choices to limit exposure to stressors. They are more responsive to their circumstances and find themselves reacting less. This means that there is less relational “clean up” to do. Over time, the window of tolerance widens and life and relationships become more manageable.

If you would like to experience the impact NeurOptimal neurofeedback can have on your window of tolerance, set up an appointment with one of our trainers today.

We also have systems you can rent and do neurofeedback at home. Email us if you prefer to rent a neurofeedback system.

Sojourn Counselling and Neurofeedback serves the Greater Vancouver and the Fraser Valley regions from our office in Cloverdale, Surrey, BC.